For a short while Iran’s cyber security threats and its use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Google and Twitter came under the spotlight. This is good, but more is needed.

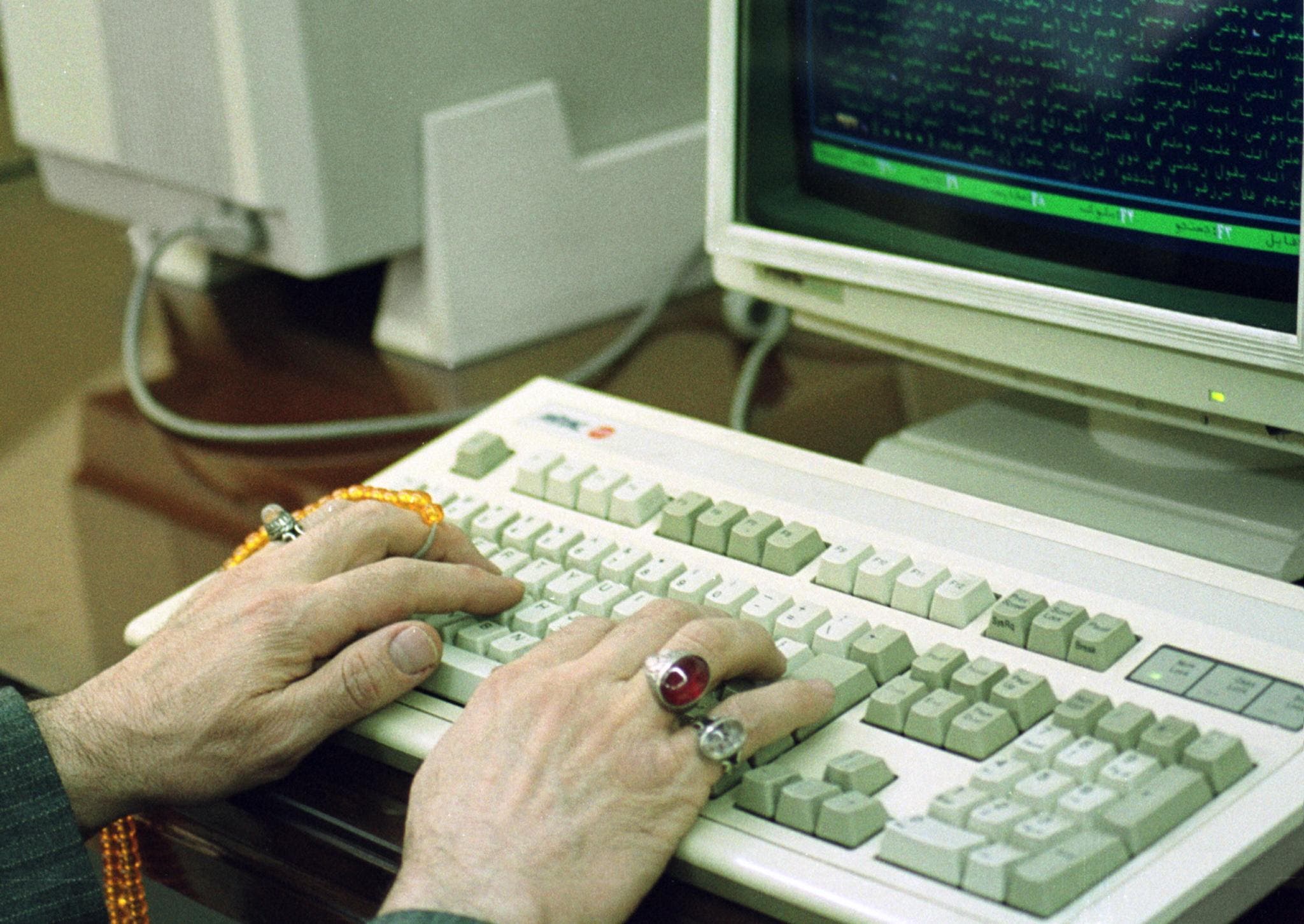

Iran runs a cyber-army and what has been unearthed recently is just the tip of the iceberg. According to Facebook, an important portion of this network was linked to an internet organization associated to the regime’s state-run TV/radio apparatus.

Reuters reports how this network is active in 11 languages across the globe, busy spreading fake news and pro-Iran political propaganda on the web. This grid, however, is only a small portion of the Iranian regime’s cyber-army, mostly directed by the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) and Bassij paramilitary force.

Dual approach

In recent years, the IRGC has also launched numerous cyber attacks targeting various banks, scientific centers, economic and industrial facilities in the United States, hacking their internet networks in the process. US officials have in response sanctioned individuals associated to this network.

Interesting is how the Iranian regime has a double standard approach in regards to the internet, considering it both an opportunity and a threat. Tehran takes advantage of the internet as a medium to promote its reactionary mentality, “export revolution” (read extremism) and also post fake news about its dissidents.

On the other hand, it’s quite interesting how the regime deprives the Iranian people of free access to the internet and its officials describe the internet as a threat for the regime in its entirety, going the distance to limit access.

A closer look

The Iranian regime’s cyber army is mainly controlled by the IRGC, centrally based in Tehran and commanded by an IRGC division stationed in the capital.

Ghasam.ir is the main website of this entity and more than 2,500 other sites are actively controlled through this medium, according to senior IRGC cyber-army officials.

Tehran’s IRGC cyber-army battalions are designed based on the regime’s needs in cyber-warfare and responses to cultural issues. At least one cyber-army battalion is established for each section of the large Iranian capital.

According to the regime’s terminology, these websites are responsible for launching “currents” on international, cultural and economic issues. IRGC Bassij members involved in social media and creating “currents” are literally creating fake news and/or behind special propaganda campaigns involving complete lies. A large number of the personnel active in this field of work are official reporters of the Bassij Press network.

Bassij cyber-army battalions have throughout the years expanded in various cities across Iran. The IRGC and Bassij have also embedded cyber-army units in all government and state entities, most importantly the state-run Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB).

The technical and communications means available in this entity allow the IRGC cyber-army to expand its activities across the globe.

The IRIB cyber unit consists of seven such battalions and 1,200 personnel, according to the IRGC-associated Youth Journalists Club. The IRIB has also launched other cyber units to confront “the enemy’s soft war” against the regime and “present to the world the objectives and goals sought through the Islamic revolution,” according to Iranian officials talking to state media.

Iran has also established cyber units in a variety of other sectors, including the country’s important colleges and universities, religious schools and even the “Cyber Hizbullah,” in charge of organizing the cyber activities of IRGC Bassij and other such units.

Controlling the internet

The Iranian regime also uses all means provided by the internet to limit the Iranian people’s access to the world wide web. Tehran’s clerics understand very well that with the free flow of information the entire crackdown apparatus imposed on the Iranian people will begin to fissure.

As a result, the regime’s ideological pillars will weaken and Iranians across the country will gain knowledge of this regime’s corruption and economic bankruptcy. This literally represents an existential threat for the mullahs’ regime.

Iran’s 2009 and the recent Dec/Jan uprisings showed how protesters use social media networks such as Twitter, Telegram and Instagram to organize anti-regime demonstrations. In response, the Iranian regime has a tendency to block or limit the people’s access to the internet and social media platforms at times of crises.

Tehran’s clerics are also known to pursue plans to launch a “national internet network” aimed at completely blocking off the Iranian people from the internet and social medial networks. This, however, has become an impossible hurdle due to the regime’s technological and financial weaknesses.

The Iranian regime’s concerns about Telegram, a popular messaging app used by over 40 million people inside Iran, is a very clear indication.

“In a discussion with [Iranian President Hassan] Rouhani we emphasized if Telegram’s vocal service is launched we will not be able to control anything,” said Hossein Nejat, deputy of the IRGC Intelligence Organization and in charge of the crackdown and arrest of cyber activists.

The Iranian regime has also failed to completely block Telegram. Senior regime officials have continuously encouraged people to use Iran-made messaging apps, only to prove a failure. The Iranian people simply don’t trust any indigenous software, knowing their information will be at the Iranian regime’s disposal immediately.

Iran’s concerns of people fully accessing the internet indicates the clerical regime’s political and intellectual failure and inability in confronting the modern world and the Iranian people’s protest movement against their reactionary apparatus.

The international community can easily stand shoulder to shoulder with the Iranian people by both sanctioning Iran’s IRIB and providing free and unhindered internet access to the Iranian people.